Cool Runnings

Rodolfo Rosini on how reversible computing can overcome the energy bottleneck to power the next generation of AI

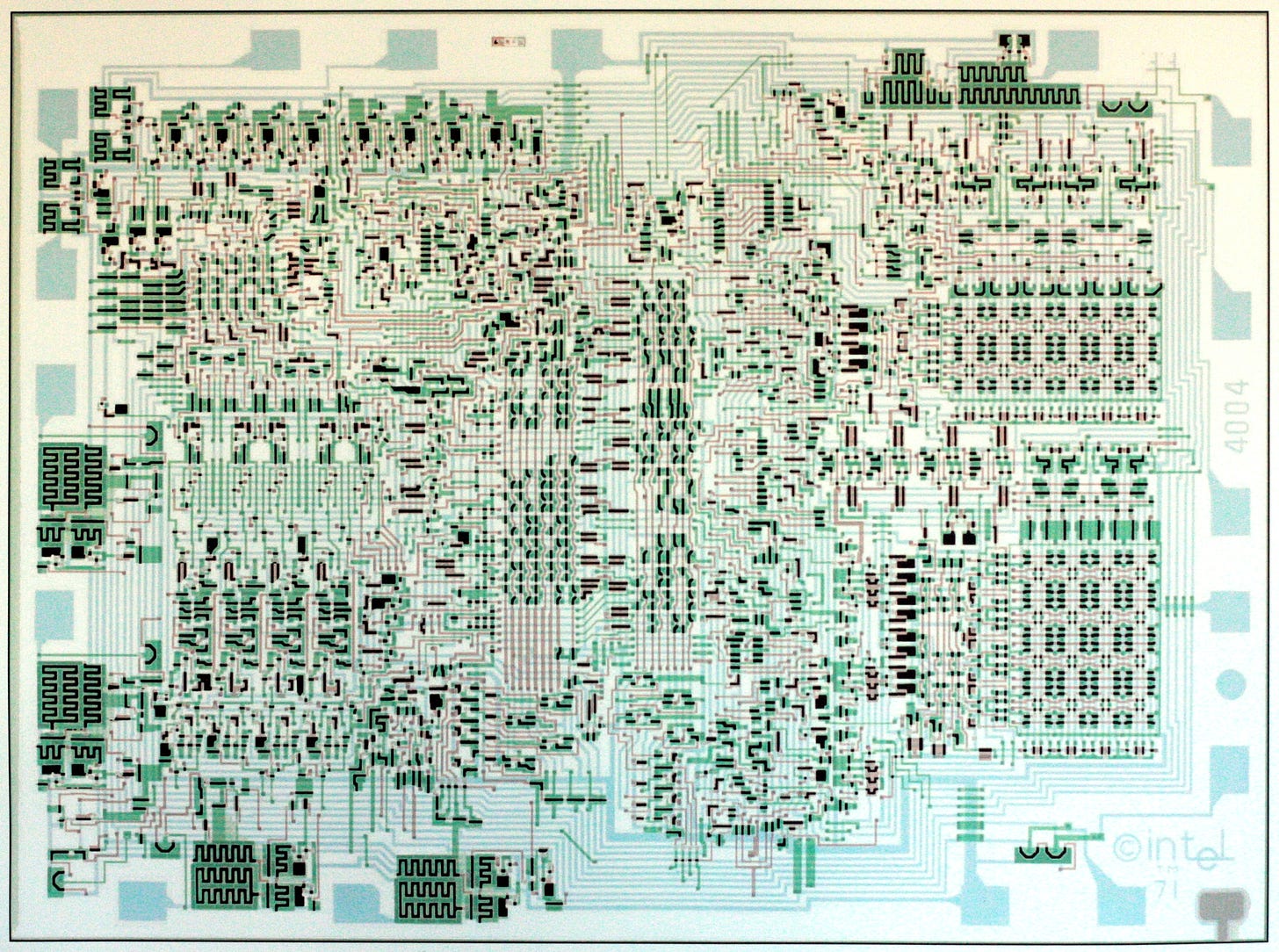

In 1965, the Co-Founder of Intel, Gordon Moore, observed that the number of transistors on a microchip tends to double about every two years. For half a century, his eponymous ‘law’ held remarkably constant.

This exponential growth in compute power has been one of the most extraordinary catalysts for change in all of human history, transforming the entire economy from analog to digital. It has allowed us to sequence the human genome, glimpse the early universe through processing telescope data, and train artificial intelligence to surpass humans in a wide range of specific tasks. That surge in processing power has granted humanity a level of agency over the physical and digital world that, only decades ago, would have been indistinguishable from magic.

But Moore’s Law has slowed — to the extent that many, including Jensen Huang, CEO of NVIDIA, have argued it is now dead. Ultimately, there is a physical limit to how small microchips can get. As transistors shrink to the size of individual atoms, engineers are grappling with challenges such as quantum interference and heat dissipation.

While Moore’s Law has been slowing down, the rise of AI has been accelerating at breakneck pace. Training and running ever more sophisticated models has become a resource-intensive process, and some are worried about the increasing amounts of electricity and land required for data centres. Current microchips are turning increasingly large amounts of power into waste heat rather than useful outputs.

Rodolfo Rosini, Founder of Vaire Computing, believes a different approach is required. According to him, the solution to AI’s energy demands isn’t just to construct more or bigger power stations, but rather to change the physics of the computer itself. Vaire is building a new computer architecture based on an idea called ‘reversible computing’, a concept that was considered a theoretical curiosity for 30 years until Rodolfo and his team decided to try to make it manufacturable.

The goal is audacious: near-zero energy computing. Vaire seeks to decouple the consumption of resources from the growth of computing. If Vaire succeeds, they will enable a huge leap in economic growth without putting enormous strain on the power grid.

I caught up with Rodolfo to discuss how reversible computing works, where Vaire thinks improvements can be made, and why the United Kingdom needs to stop fearing failure if it is to truly be a science superpower.

What we discussed

The difference between standard ‘destructive’ computing and Vaire’s reversible ‘adiabatic’ energy recovery.

How Vaire is turning reversible computing from a theoretical idea into a practical reality.

The structural challenges of building a foundational hardware company in the UK.

The mindset required to be a deep tech founder.

How the UK can best grow and scale hardware companies.

Lessons for scaling deep tech AI companies

For policymakers:

Prioritise customers over subsidies. More than just grants, deep tech companies need a market. That’s why novel funding mechanisms such as Advanced Market Commitments (AMCs) — where governments act as first customers — can be so important.

Shift from academic to outcome-based funding. Funding bodies often rely on academic consensus in deciding what to fund. Yet academic culture means they are often poor judges of commercial innovation and viability. As such, a shift toward entrepreneur-led funding models, where funding is shaped by outcomes (such as ‘more compute per watt’) rather than specific methodologies, may be more desirable.

Address the UK’s exit problem. To stop promising companies from exiting the UK, Britain needs to fix its capital markets, potentially through a specialised stock exchange for emerging technology, and remove friction for talent through fast-track visas for the best and brightest engineers.

For founders:

Seek non-disruptive integration. Innovation shouldn’t require customers to tear up existing processes and architectures. Build new architectures that use existing manufacturing processes and are compatible with legacy software. Adoption is faster when it fits existing workflows.

Validate the physics first. For foundational hardware, you cannot ‘fake it ‘til you make it’. Ensure the core concept is validated by international research proving manufacturability before you attempt commercialisation.

Focus on the big issues. Deliver solutions that matter. For example, Vaire is seeking to enable orders of magnitude more computation whilst also decoupling computation from resource consumption.

Full interview

I. Building Vaire

Vaire applies foundational physics to hardware architecture. Can you explain what you’re building and who you’re serving?

Vaire is building a new, high-performance computer architecture. Our goal is to enable the continued, affordable growth of computing power without the associated explosion in energy demand.

If you look at the history of computing, it is marked by successive ‘scaling laws’, from mechanical processing to the transistor and Moore’s Law. But Moore’s Law is ending. While the rest of the industry is trying to squeeze the last drops of performance out of existing architecture, Vaire has focused on an ‘orphan area’ of computer science: reversible computing.

The simplest way of explaining this is that chips today perform a calculation, then transistors discard the charge. This is the majority of the heat produced in a computer. The actual amount of energy performed to do computation is very small compared to the amount used each time, so by recycling the charge we can operate a chip much more efficiently, and it also dissipates less heat.

We’ll get onto the specifics of how it all works later, but for now, can you tell me a bit more about the team you’ve assembled?

Creating a new computing architecture requires a unique kind of person. It obviously needs people who have deep expertise and experience in their areas, but also people who are able to think outside the box and are willing to revisit implicit assumptions and break with their intuition. It requires the sort of creativity to find solutions to unsolved problems — but also a pragmatism so it doesn’t take decades to reach our goal. Essentially, people who believe there is a better way of doing things. Another trait that’s particularly important for an early stage startup is resilience. The startup journey is not a straight path, and so it’s important to have a team that understands that and keeps going.

Where does this concept come from?

Reversible computing originates from MIT and represents the theoretical limit of energy-efficient computing. For 30 years, it was considered non-viable. We started in 2021, and the first few years were difficult. We were in stealth mode, had only a small amount of pre-seed funding, and faced a lot of skepticism. However, international research in 2023 finally validated the concept, proving a manufacturable chip could be built.

Our architecture is perfectly suited for workloads that can be highly parallelised — that is, where a large task is broken down into small, independent pieces that are processed simultaneously rather than one after the other. This makes it ideal for AI inference, error correction, 6G and software-defined radio.

Why is this necessary right now?

Because we are running out of power. In the vacuum left by Moore’s Law, reversible computing is the only viable path forward for the $30 trillion classical compute market. It enables growth without demanding we pave the planet with solar panels or build a nuclear reactor next to every data centre.

II. How Vaire is engineering adiabatic energy recovery

This isn’t just about a more efficient chip. What makes building a reversible computing architecture different?

Our design goal was to be as minimally disruptive as possible to the ecosystem. We reuse existing manufacturing processes and materials. If we required a change to the physical silicon manufacturing, we’d spend a decade trying to convince a foundry like TSMC to let us in the door. Crucially, the hardware must be compatible with existing software, including languages from the 1950s, because customers will not abandon decades of investment and lock-in, even with a better chip.

Can you explain the difference in physics between your chip and a standard one?

It comes down to waste. In a standard transistor, the system switches electrical charge instantly — from zero to one. When the calculation is done, it effectively dumps that energy to the ground, throwing it away as heat. This wasted charge accounts for almost all of the energy consumed by a chip.

Vaire uses adiabatic reversible computing. Instead of dumping the charge, we ‘ramp up’ and ‘ramp down’ the charge slowly. This allows the energy to be recaptured and sent back to the next circuit. While a single transistor might operate slightly slower, the overall architecture operates in parallel, maintaining high throughput. The result is a dramatic reduction in energy. This has a secondary benefit: less heat means less need for the expensive, energy-intensive cooling infrastructure required by modern data centres.

So, it’s about decoupling compute from energy?

Exactly. I don’t see how we can provide power for AI without massive amounts of batteries, fossil fuels, or nuclear power — and likely all three. Our goal is to refine that energy into exponentially more units of compute.

III. Navigating Britain’s deep tech funding and policy landscape

As a foundational hardware company, what has your experience been with Britain’s funding landscape?

Our experience has been unusual compared to other deep tech startups: we have never received direct public funding from any British or American agency — instead, we only rely on standard R&D tax credits.

Funding agencies have largely misdiagnosed the problem we’re trying to solve. They were focused on AI training and probabilistic computing, while Vaire focuses on AI inference and deterministic computing, which ultimately proved to be the critical bottleneck for scale. Furthermore, Vaire is a monopoly by design — we spent three years hiring the world’s experts in this niche. Funding agencies are naturally wary of funding a single point of failure, even if that concentration of talent is necessary for a breakthrough.

What needs to change in how we fund deep tech?

We need to shift from a top-down, academic-driven approach to a bottom-up, entrepreneur-led system. The UK doesn’t have a problem creating science, but it does have a problem commercialising it. Despite this, we constantly ask academics — the very people who are part of the system that needs correcting — for their opinion on commercialisation.

Funding should instead be more outcome-based. You should accept large amounts of failure and fund whatever works to achieve a desired metric, such as more compute for certain workloads, rather than dictating the technology used to get there.

You have been quite vocal about the state of Britain’s chip industry. What do you think we get wrong here?

Chip manufacturing in Britain is a small cottage industry that fails to scale. Anyone who thinks it’s in a strong position is lying or delusional. I don’t believe there is a single chip company in the UK worth more than $1 billion. The previous incumbent, Arm, has only 30% of their employees in the UK and senior management is based in the Bay Area.

We have high energy costs, red tape preventing high-density housing for workers, and irrelevant capital markets. But perhaps most frustratingly, the government is not a meaningful buyer of advanced technology, and I’m not sure it understands in the slightest the importance of having domestic industries. We seem to prioritise the triple-locked pensions of retirees cruising the Mediterranean over the needs of engineers trying to secure our national defence.

IV. Conclusion and advice

If you were advising the Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology right now, what would be your priorities?

If we created an AI Hardware Sandbox, the priority should be infrastructure over subsidies. We should copy models like Finland’s Kvanttinova, which provides clean rooms, a quasi-foundry for quick prototyping, and cheap office space.

But the missing piece is a sophisticated customer. DARPA [America’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency] succeeds in the United States because it actually buys the end product. The UK needs a customer-driven commitment, where a public body commits to buying advanced compute if it meets certain specifications. This is more valuable for an entrepreneur than simply receiving grant money.

We need to give the absolute best technology to the people who risk their lives to defend us. Specifically for our chips, we need a 10-year supercomputing roadmap not focused on buying foreign computers, but on developing an industry that builds them here.

So the top priority should be issuing a customer-driven Advanced Market Commitment for AI hardware and advanced compute. Giving deep tech companies a sophisticated first customer is more valuable than giving them money. That’s because it forces entrepreneurs to be market-ready, and to have an exportable product rather than something optimised for grants and subsidies. In the long term, that’s a better guide for success.

More broadly, the UK needs to fix its exit problem. In order for that to happen, Britain needs to reshape its capital markets, perhaps through a specialised stock exchange for emerging technology. The UK also needs to make it as smooth as possible for the world’s brightest minds to come here through fast-track visas.

What is your final piece of advice to founders building in this space?

It’s a strategic advantage to be the only one doing a specific technology, even if it makes funding agencies wary. You also need to validate the physics. For foundational hardware, the idea must be validated by international lab results proving a manufacturable chip is possible before committing to commercialisation. Many startups fail because they spend millions on engineering before confirming the science actually works at scale.

We ask all our guests the same closing question: what’s one interesting thing you’ve read or listened to recently that you’d like to share with our readers?

I’ve been following the YouTube channel Asianometry. They have insightful videos about technologies such as millimetre-wave 5G, the hard disk drive, ASML’s extreme ultraviolet light source, and capacitors — but they also do deep dives into companies and their journeys, such as Compaq, Nissan and Sun Microsystems. As a serial founder, I find that fascinating.